This blog post is meant as supporting material to go along with the video I produced on the same topic. This is part of a series I’m doing to help give people insight into the development side of cybersecurity. Although you can read this blog post as standalone content, I did not write it with that goal in mind. This post is less thorough than the supporting video, and the quality of writing is at times lacking.

This post is about sessions in web apps, including the use of JWTs.

What’s the Purpose?

The problem we are trying to solve for here is how we verify a user’s identity (authentication) and how we know what that user is allowed to do (authorization) for a user that has already logged in. That is, the user logged in in some secure way, which I will cover in a separate post and video, and now they come back to our page and we want to be able to say “yep, I still know you, and this is what you can do.” We need some way to maintain that person’s “session”.

Architecture

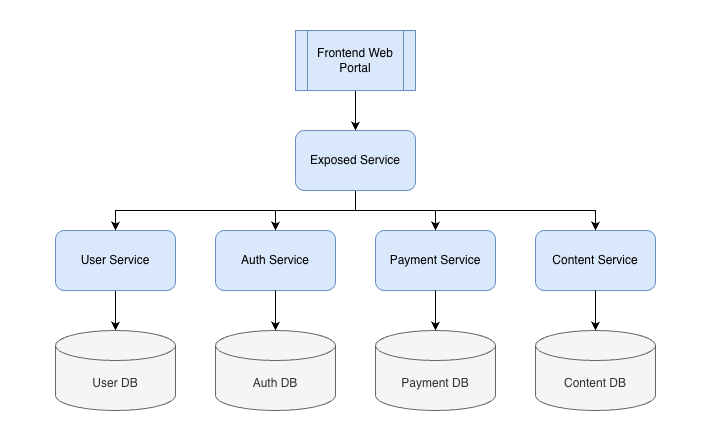

Imagine I have four different “services” that are used by my web app:

A user data service for storing and returning user data (name, email, etc.)

An authentication/authorization service for logging the user in and managing permissions.

A payment service for processing payments.

A content service for storing and retrieving content the user creates.

Instead of exposing all of those services to the frontend, one common approach is to put another service in front and only expose that one. The rest of the services would then be available only internally to the environment where you’re running your apps (ie not exposed to the internet). That looks like this:

This is a simplified version of what I run at Pistachio, and also have done for a number of different projects over the years. In this type of setup, I can keep track of sessions using a simple session ID. It doesn’t really matter what it is as long as it is sufficiently random, so I use a UUID (created using the uuid package in Go which uses crypto/rand for randomness; don’t just make your own). When a user logs in, I create the UUID, map it onto the token that identifies the user with the auth provider (say, Microsoft), and store that in the auth database. I then respond to the user by setting the session ID I created as a secure, samesite=lax, httponly cookie.

Side Note: Local Storage, Cookies, and Session Storage

There is apparently a big debate about where you store session IDs on the browser. The truth is that there is no great answer because browsers generally suck. I personally store the session ID in an httponly cookie, which means that it cannot be accessed via JavaScript; instead, the cookie is simply sent by the browser automatically with each request made by the user to my domain (given the samesite=lax property).

Other people use local storage or session storage. I don’t love that because then if someone can run JS on your page, they can steal the session ID and then do whatever they want. With that said, if someone can run JS on your page you’re kinda doomed anyway in most cases, because naturally they can make requests as if they’re the user. But I’d still argue that if there’s no good reason not to use httponly cookies then you should. Maybe XSS (cross-site scripting) is game over either way, but at least it is slightly less convenient for the attacker in some cases if they can’t just exfiltrate the session ID from localstorage. But if you need the session ID in local storage (or session storage if you want to annoy your users), it isn’t the end of the world.

Request Flow

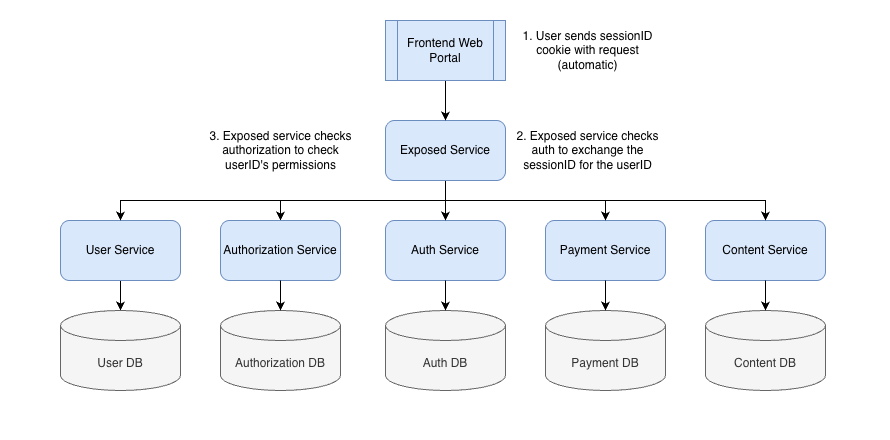

Getting back to the architecture discussion: Now that the user has the session ID stored in his or her browser it is included automatically in every request the user makes to my backend. So when the exposed service gets a request, it first checks the session ID cookie. If it finds one it sends the value to the auth service and gets back the user’s identity (or an error). Once it figures out who this user is, it then moves on to check whether the user is authorized to make this request, and if so, does whatever logical steps are required. I’ll come back to authorization in a second.

JWTs

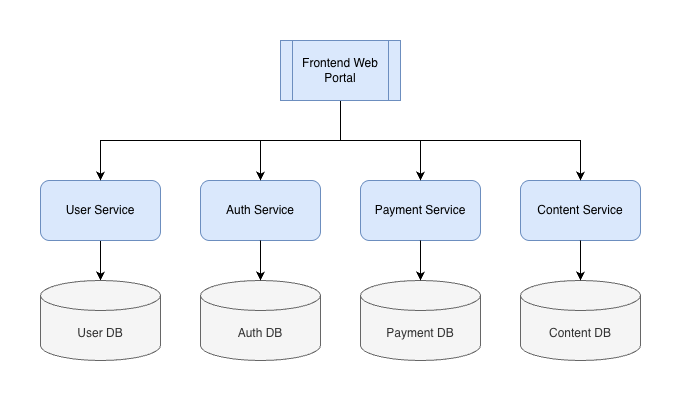

You might be wondering why I haven’t mentioned JWTs, so let’s talk about that. Imagine I have the same architecture I outlined further above, but instead of a single exposed service, I instead exposed all of the services directly to the frontend. That would look like this:

In this world, there is a problem. You need each service to know who the user is, but that information is only stored in the auth database. One option is to have each service connect to the auth database directly, but that is of course a terrible decision. Another option is to have each service make requests to the auth service. Slightly better, but still chaotic and messy.

That is the problem JWTs are intended to solve. Instead of creating a session ID, you create a token that contains information about the user (like their user ID) and their permissions and sign it using a private key, then send that to the browser. Then, on each request, the service requested checks that token and verifies it is valid using the public key. That way, each service can know who a user is and what they can do without having to make requests to some shared state.

Cybersecurity people often believe that JWTs are somehow more secure, but the reality is that they’re not solving a security problem. They’re solving a “how do we do security in a distributed stateless manner” problem. Which is fine, but if you’re willing to just have a shared state… JWTs are actually worse. Why? Because if you have a session ID that you check against a database on every single request, you know you always have the most up to date information. With a JWT, a service might see a valid token even if the auth service has since removed permissions or logged the user out. There are workarounds to that, more or less involving re-introducing state (a database) into the equation. But the important thing here is that JWTs are not a security improvement. If you can check your database to get a user’s identity and permissions on each request, you should. And then there’s no use for JWTs.

Authorization

Back to the way I do things: As I explained, on each request I make a check to get back the user’s identity from the auth service. At the start of this I simplified the setup to explain that I use auth for both authentication and authorization, but that isn’t exactly true. I usually have a separate system for authorization, which stores what permissions a user has over which entities.

So, after making a request to the auth service, my “exposed service” will then request authorization information. So the full set of steps looks like this:

Session Rotation

It’s pretty common to hear cybersecurity people say things like “sessions should be short-lived”. And like, yea, if you’re logging someone into a banking app that is absolutely true. But think about all of the services you do on a daily basis. If each one of those SaaS applications logged you out after 30 minutes of inactivity, you’d be pretty pissed. It would be totally unworkable to have to log in to GitHub, Microsoft, Trello, and Figma every 30 minutes. So while it would be a security improvement, it would also become a UX nightmare. Of course, if you’re using JWTs you probably do want a short-lived token, but that is because invalidation is hard; if you want to keep users logged in so you don’t ignore them, you’ll also need some longer-lived token as well.

My approach to this problem is to have a session ID that lives for a couple of days, but also invalidates when it gets used and replaced with a new token. That means that an unused session ID lives for a few days, but an attacker finding a used session is useless.

There is one caveat to this: You can’t actually make session IDs truly single use because most web apps make concurrent requests. So the exact logic is that when a session ID gets used, we set it to expire within a few seconds. That means that an attacker that somehow intercepted a used session ID does have a tiny window for opportunity. Better than using the same session ID over and over, though.

Nothing is perfect in this space. It’s all about tradeoffs and deciding what level of risk to take in exchange for improved UX.

What Can Go Wrong

Let’s jump into some code. I’m not going to bore you with basic examples of how to write code that reads and sets cookies, or checks values in redis. However, the code I do want to look at is the authorization part, as that is one place where things can go very wrong.

When we talk about authorization, we often talk in terms of roles. For example, “User 123 has the content.create role.” But there’s a third element to this, which is the entity that role relates to. User 123 can create content, but not in other people’s accounts! So you have to ask a more specific question than just “what is this user allowed to do?” You have to ask, “Is this user allowed to do this on this account?” And that’s a bit harder.

So let’s look at some code. Say I have one route, CreateContent, that requires admin permissions over the specific org the content will belong to. I might set up some middleware like this:

func (s *Server) addAuthorizationMiddleware(r ...*mux.Router) { p := middleware.Permissions{ Routes: map[string]map[string][]string{ createContent: {orgID: []string{permission.Admin}}, }, P: s.Authorization, } for _, sr := range r { sr.Use(p.VerifyAuthorizationMiddleware) } } const orgID = "orgID" // Routes const createContent = "CreateContent"

Then my route looks like this:

// Content authenticatedAPI.HandleFunc("/organizations/{orgId}/content", handler.CreateContent(s.Content)).Methods(http.MethodPost).Name(createContent) s.addTracingAndMetricsMiddleware(authenticatedAPI, unauthenticatedAPI) s.addAuthMiddleware(authenticatedAPI) s.addAuthorizationMiddleware(authenticatedAPI)

The authorization middleware then is saying “for the authenticated user making this request” (which has already been checked by the auth middleware), check if this user has admin over the provided orgID (or whatever entity identifier is required for this route):

type Permissions struct { Routes map[string]map[string][]string // map[routeName]map[entity][]role P user.EntityPermissionGetter } // VerifyAuthorizationMiddleware verifies if a user is authorized to take the requested action. func (p Permissions) VerifyAuthorizationMiddleware(next http.Handler) http.Handler { return http.HandlerFunc(func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) { routeName := mux.CurrentRoute(r).GetName() var entityIDVariableName string var requiredPermissions permission.List for key, value := range p.Routes[routeName] { entityIDVariableName = key requiredPermissions = value } ctx := r.Context() userID := user.GetUserID(ctx) if userID == "" { handleError( ctx, w, fmt.Errorf("error, userID empty in handler %s", routeName), http.StatusInternalServerError, true, ) return } entityID := mux.Vars(r)[entityIDVariableName] if entityID == "" && entityIDVariableName == "userID" { entityID = userID } // get the users permissions userPermissions, err := p.P.GetUserPermissionsOverEntity(ctx, userID, entityID) if err != nil { handleError( ctx, w, fmt.Errorf("error getting user permissions in handler %s: %w", routeName, err), http.StatusInternalServerError, true, ) return } // error if the user still does not have one of the required permissions if !requiredPermissions.IsAuthorized(userPermissions) { handleError( ctx, w, fmt.Errorf("error, user %s lacks permissions for handler %s", userID, routeName), http.StatusForbidden, true, ) return } // put into context for error handling and stuff ctx = context.WithValue(ctx, permission.Key, userPermissions) next.ServeHTTP(w, r.WithContext(ctx)) }) }

In the handler, it looks like this:

// CreateContent godoc // @Summary Modifies content for a given org. // @Description Modifies content for a given org. // @Tags Content // @Produce json // @Success 204 // @Failure 400 {object} client.ErrorCodeResponseBody // @Failure 500 {object} client.ErrorCodeResponseBody // @Router /organizations/{orgID}/content [post] // @Param content body user_request.Content true "The content to create." func CreateContent( c user.ContentCreator, ) http.HandlerFunc { return func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) { ctx := r.Context() var content user_request.Content err := json.NewDecoder(r.Body).Decode(&content) if err != nil { helper.HandleError( ctx, w, fmt.Errorf("error decoding content in CreateContent handler: %w", err), http.StatusBadRequest, true, ) return } err = content.Validate() if err != nil { helper.HandleError( ctx, w, fmt.Errorf("error validating content in CreateContent handler: %w", err), http.StatusBadRequest, true, ) return } err = c.CreateContent(ctx, content) if err != nil { helper.HandleError( ctx, w, fmt.Errorf("error creating content in CreateContent handler: %w", err), http.StatusInternalServerError, true, ) return } w.WriteHeader(http.StatusNoContent) } }

There is a pretty big security problem here. Go ahead and take a minute to see if you can find it. Don’t worry too much about the Go syntax, the security problem is more of a logical flow problem that you can spot if you just vaguely follow the code. (It’s also possible there are other security issues here, as this isn’t production code, I just wrote it for this demo.)

The Problem

The issue here is that, when I check authorization, I check the orgID in the route to see if the person has admin permissions in that org. But then, the request I send to the content service uses the request body. So, if your an admin in one org, you can then send a request to create content in your org, but use the orgID of someone else’s organization in the content body. Given I am only sending that to the content service, it will then create content in that other org.

So what’s the fix? It’s super easy. For example, you can just set the orgID from the path and set it to the orgID in the body:

content.OrgID = mux.Vars(r)["orgID"]

Alternatively you can check if the two values are equal and error if they aren’t (that might be safer, because then you catch cases where those values don’t match). Regardless, you have to do something. And that is where mistakes can come from. If you had to point to the “weakest link” in my authentication and authorization setup, it’s probably this. This one line separates secure code from a massive vulnerability. (Note: I do actually have some workarounds to catch this even if a dev forgets, but they’re very weird custom stuff I’ve written and not something I’d expect to find in most codebases.)

Of course, there are other frameworks or approaches that handle this differently. For some applications, this part might be impossible to screw up, while some other piece might be hard. But I thought it would be helpful to share this example to show how things work in many of the systems I build, knowing this is a common pattern. So, if you’re looking for vulnerabilities, maybe look at endpoints that identify the resource both in the path and in the body (or try just adding it to the body anyway) and see what happens.

Conclusion

That’s it. Like I said, this blog post is supporting material to my video recording where I talk through these topics and more. Still, if you only read this post, I still hope it was helpful. I’ll hopefully have another recording out soon, this time on the authentication / oauth2 step.