I don’t know when the phrase “tech adjacent” was first used or where it came from, but looking at the world today it feels pretty pointless. Without making any claims about the distribution of the global workforce, I think it is fair to say that most people reading this blog are at least adjacent to someone who is adjacent to tech (“tech adjacent adjacent”), and at some point will end up having to work directly with people in tech. Such an opportunity is usually seen as a good thing, which is why it is so common to hear non-tech people say that they want to learn a bit of programming or that they are trying to understand the core principles behind technology. Being totally ignorant of tech is not great for a person’s career.

But if you are non-technical, what skills do you need in order to work effectively with people in tech? There are some obvious soft skills, like being a good listener and not being an asshole, that will help you out. But if we go beyond that, what makes a non-tech person good at working with tech?

I would argue that if you are trying to improve your knowledge of tech in order to work more effectively with tech workers at your job, the key skill that you should focus on is the ability to take a particular problem and identify which part is the “hard part” technically. In this blog post, I explain why that skill is so valuable and necessary, and how you can train yourself to get better at it.

Misunderstanding the Hard Part

Imagine you work at an ecommerce company as the head of marketing. You realize that when a customer abandons a purchase in the middle of checkout, you are not doing anything to get that customer to come back. You come up with the idea of sending out an email to the customer a few days later asking if the person would like to complete his or her purchase. The only problem is that you do not know technically how to make that happen.

Now imagine a salesperson comes along and pitches you on a new CRM system. According to the salesperson, the CRM system is capable of “creating personalized journeys based on customer interactions”. That sounds like exactly what you want! You need to trigger an email based on a customer’s behavior on your ecommerce site, and you need that email to at least reference the item the customer was attempting to purchase.

Now, when you go pitch the CRM system in question to the tech people at your company (or when you tell them you already bought it, depending on how technically mature your organization is), they are not going to be impressed. That is because the tool you bought is not solving the hard part of the problem.

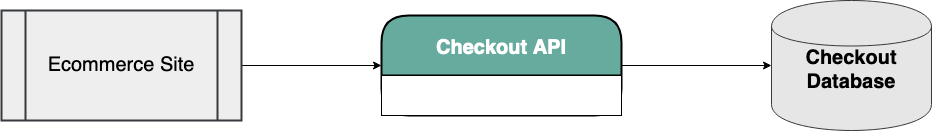

To see why, let’s start with what your tech probably looks like today. You have an ecommerce site, and you have an API that gets called whenever someone adds an item to his or her shopping cart. That API stores that information in a database. In other words, your tech looks like this:

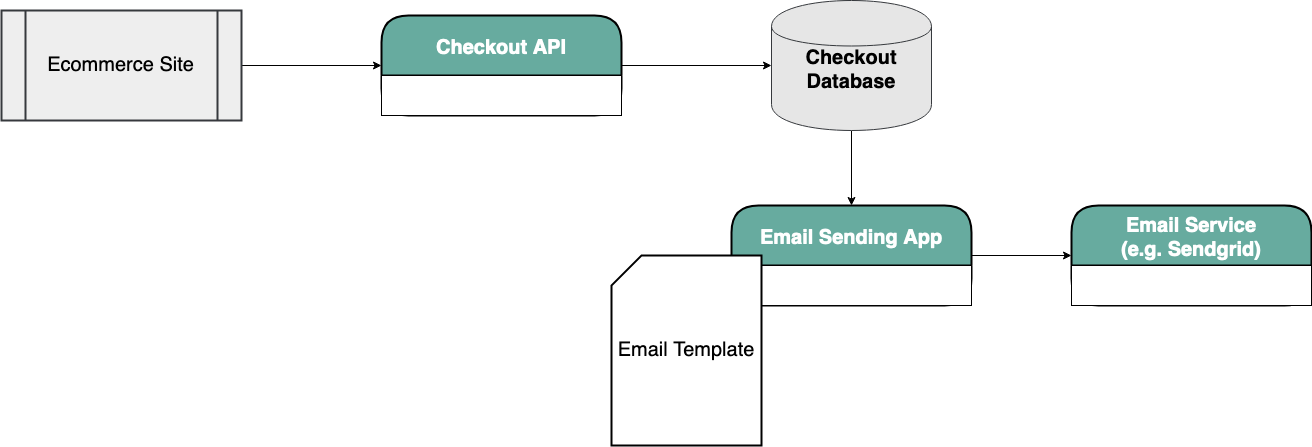

If your developers are absolute maniacs, they could just write a simple application that connects to the same database, checks for checkouts that fit the criteria you specify, fills in data to some html template they create with the text you want, and sends an email off to some email service. They could probably make that happen with a day or two of work. Like this:

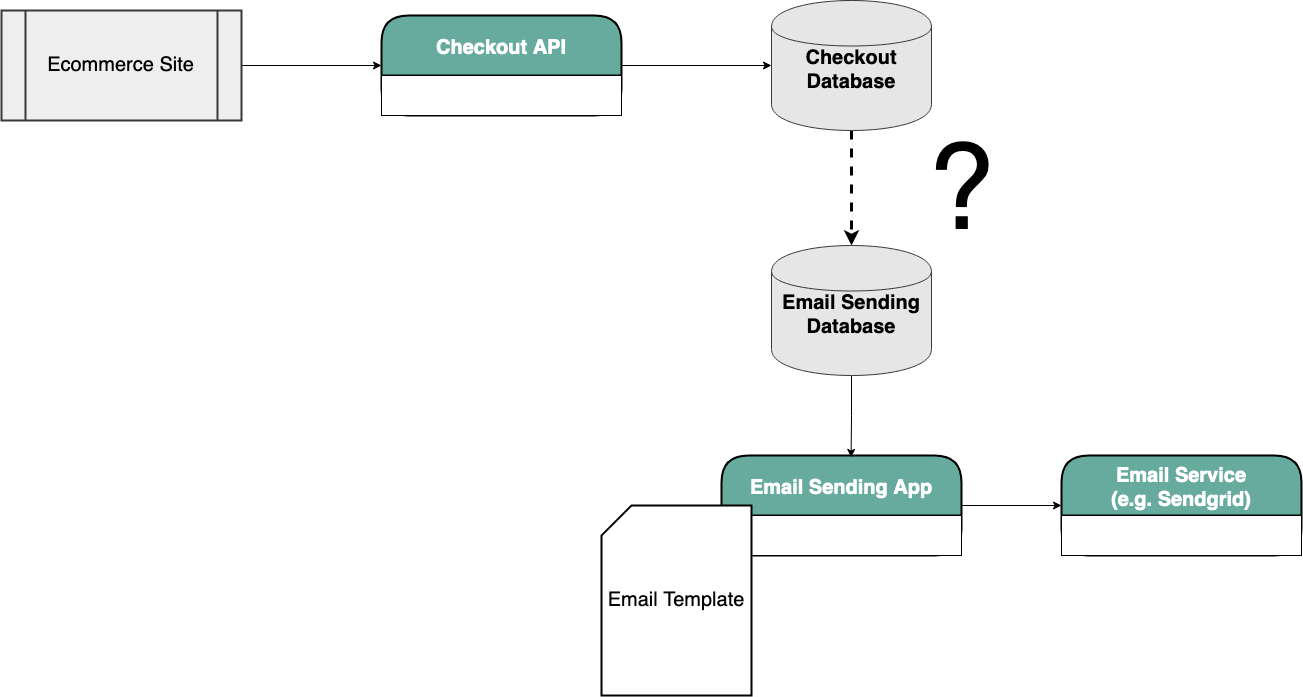

Hopefully your developers are not maniacs, though, and recognize that doing this means that some bad code in your email sending app could take down your entire site’s checkout, which is less than ideal. So then the problem starts to get harder. Somehow, the developers need to get the data out of the checkout database and into something else dedicated to this purpose.

The question mark and the dotted line is the “hard” part here. That is the problem the developers need to solve. They need to figure out how they are going to get the data they need from the checkout database into some other system without negatively affecting the checkout database itself. Once they have a plan for that, they were never going to struggle to find the relevant customers to send to, fill an email template with the relevant data, or send the email. However, those are the pieces that your CRM system provides. In other words, you found a system that solves the wrong part of a task, because you misunderstood which part is hard. (Also, for what it’s worth, getting data into something like Microsoft Dynamics is generally way harder than getting it into a Postgres database.)

Why It Matters and How to Improve

The above example might seem silly, as you are probably thinking you can get around the problem by just talking to the tech people first. You can (and definitely should)! But think about this in the context of actually trying to come up with new ideas to drive the business forward. If you are not able to correctly identify which part of a technical problem is “hard”, you won’t have any clue what is easy either. To you, it will all seem like one blob of “tech”; you will be the person asking for features in the XKCD comic about the bird app.

And let’s be honest: Even if you are the humble person who always says, “I don’t know, we should really talk to the tech folks about this,” there is always going to be some other person in the company who won’t do that. You won’t be known as the non-technical go-to on tech in the company if you are just pointing people at the tech department. You will be known as the boring person who doesn’t know tech, as unfair as that is. In other words, you actually need to know enough to be able to say “sorry that is hard” or “you are solving the wrong problem”. And if you can go further and come up with new ideas that are plausibly not that hard, more power to you.

So how do you develop the skill of identifying which part of a problem or task is hard? I think there are two parts. The first is the easy but boring answer, which is to listen more. If you do talk to tech people at work, ask them to explain how they solved certain problems. Developers think they hate meetings, but by and large they actually just hate listening. They will gladly talk at you about tech.

Second, start solving problems on paper. “Knowing a little bit of Python” isn’t going to get you very far in actually cooperating with tech people, but if you can identify the real steps required to solve a problem, that will. So to return to the above example about sending emails, before you go over to the tech department, write out a list of steps that you think would solve the problem. Start at a high level, for example:

- Get data about customers who abandoned a purchase, with details of that purchase, and store that data.

- Have an app check that data daily and pull out customers with an abandoned purchase from X days ago.

- Take that list of customers, and for each, insert the customer’s name and list of items into an email template.

- Send the email.

Then start to break each step down further. How are you going to get the data? When does it get stored? Etc. The key is to remove the magic from each of the steps, and describe a more concrete process. Ultimately, your solution will likely suck, but it will also reveal some of the challenges involved in solving the problem at hand.

You don’t need to show your solution to anyone. If you just take the time to do this every time you have an idea, and then get someone at your work to show you how they actually solved it, you are going to learn a lot about which parts were hard and which parts were easy.

Leveraging Your Skills

You might think that this all sounds like a lot of work. It is far easier to just read an article about web3 and then talk about innovation and disruption, after all. People might even be fooled into thinking you know tech that way! However, it is important to understand that developers have a super power, which is their ability to create. If you are able to effectively work with tech at your company, you are going to form a shared understanding with the developers, and that is a valuable alliance to be a part of. In other words, developing the skill of understanding which part of a problem is hard is worth the effort.